Grangetown industry

Early industry

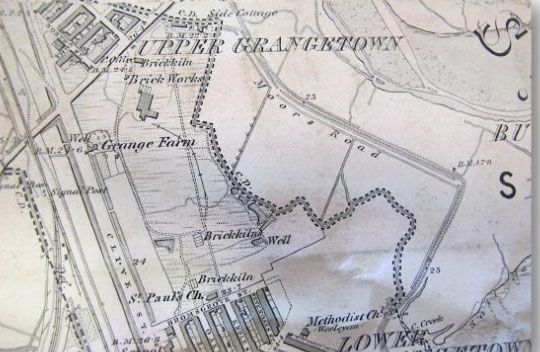

Brickmaking was the earliest industry in the area and was established early in the 19th century, taking advantage of the "marl" clay under the ground in Grangetown. London industrialist George Knight rented 22 acres of land to dig clay pits, brick-making sheds and also establish lime kilns for fertiliser making.

The Windsor estate bought the business off him in 1855, as it looked to build homes and businesses in the area. A track linking the parts of the business is roughly where Paget Street was later built. Under the Windsors, the business produced 330,000 bricks in 1856, and within 15 years, at a peak was producing 1.5m bricks a year. Grangetown was literally built from the ground underneath it.

The brick yard by the mid 1860s was assuming "an animated appearance." Durham-born James Stubbs, the brickyard engineer, lived in the house there with his family (he also ran The Grange pub for a while). By 1865, hand-made brick-making was commencing "in earnest while Knight and Stubbs patent machinery is turning out a large quantity every day," reported the Cardiff Times. Although the February frost in 1866 led to a fortnight's closure and the bricks put out to dry in the field had to be brought back in for re-casting. The brickworks was roughly where modern day Redlaver Street and Paget Street is now. There was also another brickworks near present day Sevenoaks Park.

The David and Sloper tannery was opposite the site of the present Sevenoaks

Park (pictured right). It was founded by curriers Charles William (CW)

David and John Sloper in the 1860s, who remained in charge until their partnership

was wound up in 1881. David (1818-1883) and Sloper (1823-1905) both served on

Cardiff town council, the former serving as deputy mayor and the latter as an

alderman. Sloper was born the son of a Monmouthshire surgeon and became an apprentice

tanner before moving to Cardiff. The road in which the tannery stood by the

1920s carried Sloper's name. His business interests with Llandaff-born David

extended to a colliery and the board of the town savings bank, while David had

a shop in Duke Street established by 1858, with a combined business premises

later at 5 Working Street. When they died, the bachelors left a considerable

fortune - David £37,439 and Sloper nearly £22,000 in their wills.

The tannery by the end of the first decade of the 20th century became known

as Grange Mills and Gripoly Mills, before finally becoming a small business

park in the 1980s.

The David and Sloper tannery was opposite the site of the present Sevenoaks

Park (pictured right). It was founded by curriers Charles William (CW)

David and John Sloper in the 1860s, who remained in charge until their partnership

was wound up in 1881. David (1818-1883) and Sloper (1823-1905) both served on

Cardiff town council, the former serving as deputy mayor and the latter as an

alderman. Sloper was born the son of a Monmouthshire surgeon and became an apprentice

tanner before moving to Cardiff. The road in which the tannery stood by the

1920s carried Sloper's name. His business interests with Llandaff-born David

extended to a colliery and the board of the town savings bank, while David had

a shop in Duke Street established by 1858, with a combined business premises

later at 5 Working Street. When they died, the bachelors left a considerable

fortune - David £37,439 and Sloper nearly £22,000 in their wills.

The tannery by the end of the first decade of the 20th century became known

as Grange Mills and Gripoly Mills, before finally becoming a small business

park in the 1980s.

| Elliott and Sons Rope Works

Cardiff Rope Works was opened in 1863 by ship's chandler Richard Verity and ship owner William Coward, under a 99 year lease. It boasted that it could produce ropes from half an inch circumference to 24 inches. At its peak, it employed 60 men, women and boys and its "rope walk" was one of the longest in the UK, being 170 fathoms (1,020ft) long. Verity died in the same year aged 36 and the business was put up for sale, along with two cottages on the site, in 1865.

The works were close to the Cardiff to Penarth railway, which officially

opened in 1878. And it caused something of a problem one July night

in Grangetown, when hot cinders from a passing train were blamed for

starting a fire in 1886 which burnt down half of the rope works, backing onto

the track. The business, now called Messrs Elliott and Sons, and was owned by Alderman J Elliott,

made rope out of hemp - just off Penarth Road.

At 3am on the night of the 17th July, a watchman at Grangetown gas works

opposite spotted the fire. It had taken hold of the wooden buildings which

housed the machinery and store of hemp. The manager, Sunderland-born Samuel

Waugh, 37, who lived on site with his wife and three children, was roused

and sent his teenage son Robert - later the assistant manager - for the

constable. The steam-driven fire engine with nine of the fire brigade

had arrived within 20 minutes. The best they could do was save the engine

house, new rope shed and the manager's own house. "Whenever the flames

burst through, the smell from the burning hemp was so strong that anyone

approaching was driven back by the choking sensation coming from the inhalation

of smoke," reported the South Wales Daily News. The rope yard,

machines and hemp waiting for tarring were destroyed, with just "ironwork

bent and broken left" and damage estimated at £1,500. Luckily, they were

insured. Cinders had started grass fires on the embankment earlier in

the summer. "It is supposed that a hot coal from one of the engines on

the Penarth railway had fallen on the roof of the wooden shed and set

it on fire."

The works carried on and supplied the docks, including one rope weighing two tonnes and being 25 inches in circumference - claimed in 1908 to the biggest ever made in south Wales.

|

Grangetown Gas Works

The works, off Ferry Road, opened in 1863 and was a big employer.

Cardiff Gas Light and Coke Co was formed in 1837 in Whitmore Lane/Bute Terrace

by an Act of Parliament and chaired by Charles Crofts Williams, who became mayor

of Cardiff. As the town expanded, there was need for a larger works - with land

acquired at Grangetown in 1859, with the works opening in 1863 - connected to

the Bute Terrace works by an 18 inch main. By 1870, the works was supplying gas

to light up the new suburbs of Cogan, Whitchurch, Radyr and St Fagans. The works

expanded, with the purchase of some of Grange Farm's land and land once used by

Grangetown iron works. It was not universally popular. There was some opposition to the price of gas, while others locally in 1869 complained to Parliament at the time of the Cardiff Gas Bill about the smell. Mr Salt, a local builder, said lots of tenants had given notice - some leaving without paying rent. A local vicar and schoolmaster also objected.

Even the company's own history in the 1930s admitted workers in the early days

toiled "in dusty, dirty and confined conditions," as they handled coal and ashes

by hand. Later the works would become more automated. The works had five gas

holders, the largest with a 1.5 million cubic ft capacity; 16 boilers, two cranes

and 24 pumps. Water for the works would be pumped from a 407ft deep well. The

coal was burned through a process to produce gas, with 400 tonnes of coal carbonised

a day. The coal would arrive by train at the works' sidings. When coke was removed

- it was loaded onto wagons. The crude gas was condensed, drawn through exhausters,

scrubbed and washed of impurities and the sulphur removed, before it was stored

in the holders, ready for supply.

The works had a sports field for its football, cricket and baseball teams -

there's another article below with some memories. There was also a plaque to gas workers who died in World War One, which now resides in the Grange Albion club.

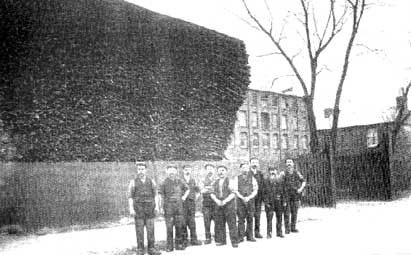

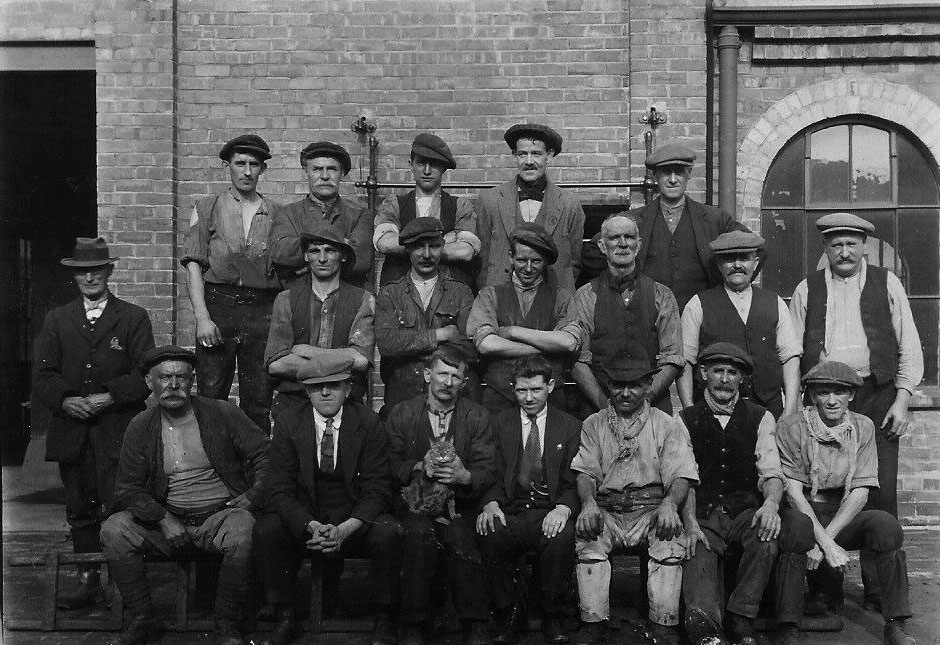

Thanks to Michael Barry for sending this

evocative photo of workers between 1900 and 1910. His grandfather Thomas was

a stoker in the gas works and is on the extreme right of the middle, wearing

a flat cap. Notice the man in the middle holding a cat!

This photo was sent in by Vic Owen, who was station engineer at Grangetown Gas Works between 1964-1970. It was taken in 1963. Anyone who has any memories of the gas works at this time - and remembers the photo being taken, let us know

Dad's Army - the Home Guard at the Grange gas

works in the 1940s.

Other industries were clustered near the gasworks.

More short-lived and troubled was Grangetown Iron Works (next door

to the gas works and opposite York Street (Place)/ Ferry Road and on the site

of Ikea). In 1865, the "magnitude" of the buildings was on a scale

the Cardiff Times found "quite surprising. " "Besides

the works already under cover are the walls and foundations of very extensive

sheds for machines. These sheds, like the finished ones, are to be covered with

corrugated iron and when finished will form an establishment not equalled by

any in the neighbourhood." But it did not last, with the whole industry

in south Wales suffering in the 1860s from depression. The ironmaster for a

time was George Levick, the son of the ironmaster Frederick who had run much

larger ironworks in Blaina and Nantyglo. There's a report of 150 workers attending

a dinner at the Princess Royal pub in Hewell Street to celebrate his wedding

in 1871. When it was put up for sale in 1873 the works had a price of £10,000.

It had 12 pudding furnaces, four steam boilers, six coke ovens, set in six acres

of land, with its own railway sidings. It could produce between 300 to 400 tonnes

of finished iron a week. There were no bids at the 1873 auction. It always struggled

and had closed down for good by 1881 after numerous changes of ownership and

eventually the site was taken over by the expanding gas works.

Saltmead industry - from soap to cigars

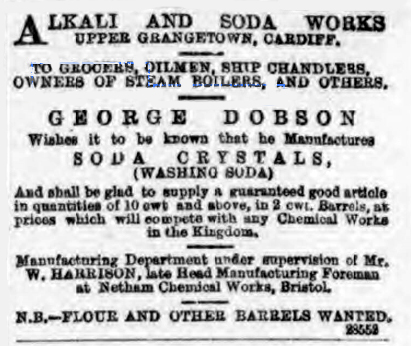

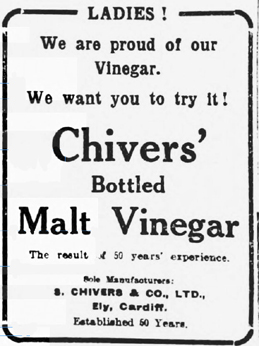

An advert for Dobson when the business set up, and a later ad for Chivers after the move to Ely

From 1879 until the late 1890s there was was a small chemical works - Grangetown or Cardiff Alkaline Works - or George Dobson Ltd. It produced ammonia and washing soda crystals and exported to Russia and Egypt for the tanning trade. It was owned by George Dobson, a one time African explorer who set it up after making money in the United States. He had a larger works in upper Grangetown - at 57 North Clive Street and for a time a smaller one in lower Grangetown. He faced problems of debt in the mid 1880s when prices fell. He sold off plant and 60 tanks after he stopped making soda crystals and soap in 1886. He later became managing director with the chairmanship being taken by George Tregaskis, and then there was a bankruptcy petition in 1894.

Right next door to the alkaline works for most of this period was Chivers vinegar factory. It was set up by Samuel Chivers, who had been working for his father Jotham, a chemical manufacturer who had an acetates and solvents works in Pontypridd - Chivers, Todd and Chivers (formerly Charles) - from the 1850s, employing around 50 men. A fire burnt down the plant which may have led to a move to Cardiff. Samuel had been employed as a vinegar agent. The Grangetown works made vinegar and from the late 1870s, apart from a brief period in the 1880s, it made jam too. Chivers ran the Grangetown business with Isaac Padfield and lived at Llandough. He had the misfortune of a cart accident in 1883 when he and a relative were thrown into the road. Chivers with a bone protruding through his trousers had to have a leg amputated; he then rather curiously had the limb buried at Cathays cemetery - preceding the rest of him by 34 years! You might have wondered whether this factory had anything to do with the famous Chivers jams and jellies. Well, there is no connection whatsoever but it didn't stop the Cambridgeshire firm taking the Cardiff namesake to the high court in 1900 to try to stop them trading under the same name. Both companies by then were long established and the judge ruled that "Cardiff" was clearly marked on packaging, so dismissed the case. Two of Samuel's sons Ernest and Samuel Leonard later took over the business and it moved to Ely in the 1890s, where it was a well known fixture until the late 1970s.

The site of the vinegar factory would become one of the most well known names and largest Grangetown businesses by

the turn of the 20th century was the Freeman's

cigar factory, which had opened in North Clive Street by around

1903, becoming a major employer of women. It later moved to bigger premises

in Penarth Road, before closing sadly in 2009.

Another business which literally went up in flames in August 1896 was the

Saltmead Candle Factory, owned by the Harold Davies and his brother.

The caretaker Thomas Johnson had locked up the building for the night and gone

to the Baroness Windsor pub, 300 yards away, when the blaze began. The building

was wooden and there was several tons of tallow, grease and candles inside and

it was "a total wreck" within half an hour. The damage was estimated

at £1,500 with only £500 covered by insurance. Mr Davies suspected

arson and "for some time past he had been annoyed continuously by incursions

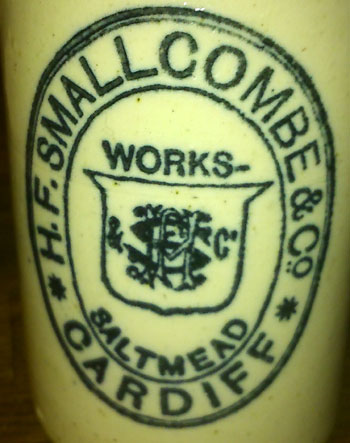

being made by some person or persons unknown to him upon the premises."  Other pockets of smaller business included HF (after Harriett, later under

her husband Joseph's name ) Smallcombe, mineral water manufacturer. They were

based at 38 Clare Road - now a signwriter's shop - and also lived at 12 Allerton

Street. The business was established by the late 1890s (see bottle, above

right) and was still operating by 1911.

Other pockets of smaller business included HF (after Harriett, later under

her husband Joseph's name ) Smallcombe, mineral water manufacturer. They were

based at 38 Clare Road - now a signwriter's shop - and also lived at 12 Allerton

Street. The business was established by the late 1890s (see bottle, above

right) and was still operating by 1911.